Dunbar's number for learning

How can understanding our ‘monkey sphere’ help us design learning experiences and the teams that deliver them?

Robin Dunbar is a British anthropologist. He is famous for the number 150.

He discovered a relationship between the size of primates neocortex relative to their body and the size of the social group they hang around in.

The neocortex is the part of the brain associated with cognition and language.

If you extrapolate the behaviour you see in different primates and apply this ratio to humans, the social group we are comfortable with is ~150.

Some have referred to this as your ‘monkeysphere’.

This number can be seen through history as a number humans are comfortable with:

Roman legions were first divided into maniples of 120 men and later condensed into cohorts of 480

English villages in the 11th century were around 150 people

Research into Christmas card lists has also suggested this number is significant

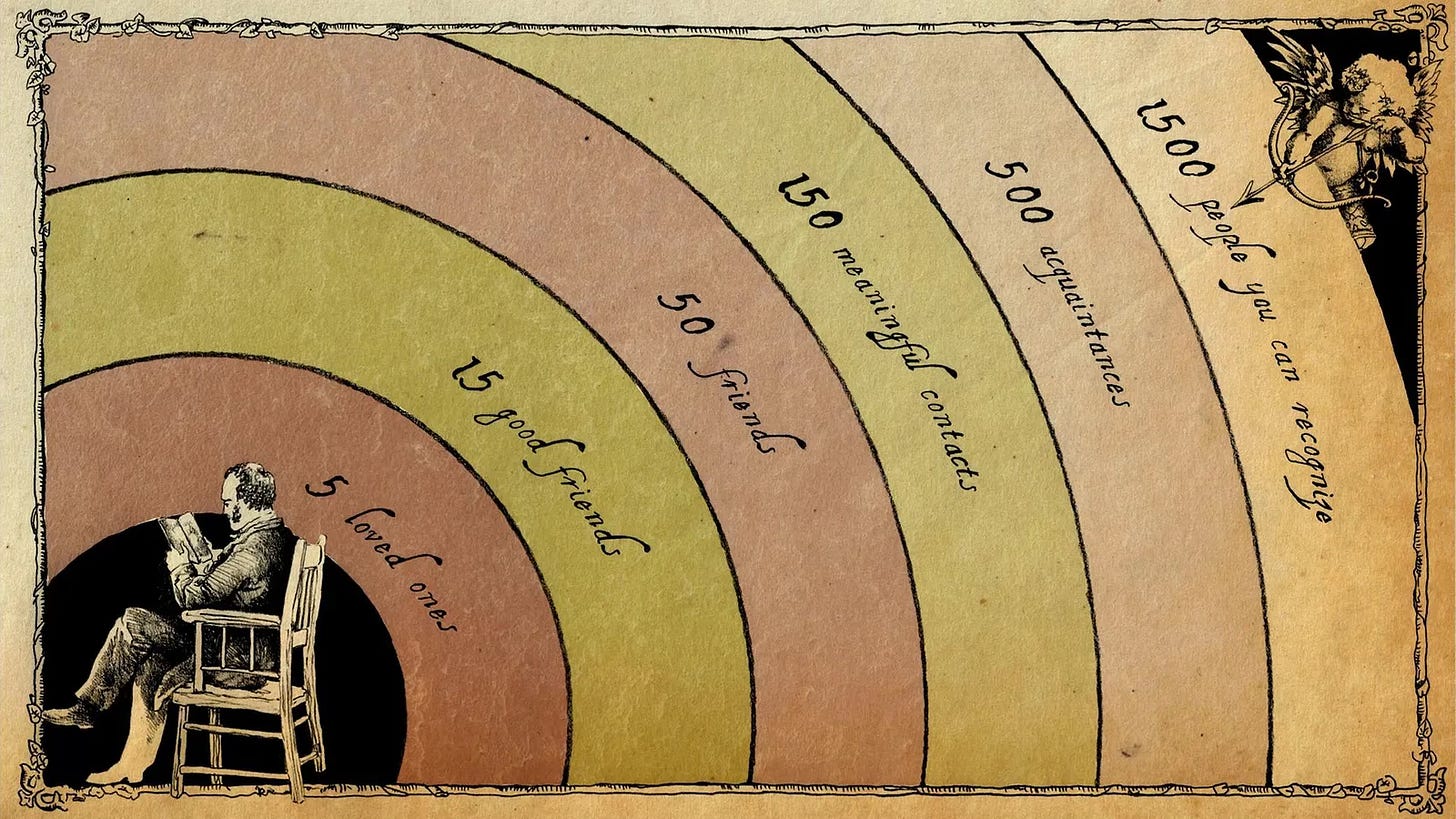

But as well as the headline number of 150, Dunbar’s research identified several other important groupings:

5 loved ones

15 good friends

50 friends

150 meaningful contacts

500 acquaintances

1500 people you can recognise

These numbers vary a little for different people. How extrovert they might be or whether they are fortunate enough to have an assistant to take on the emotional labour. Younger people who use the internet a lot also tend to have slightly larger social networks than older folks.

However, the most significant factor is how often people interact with these groups. Loved ones are in contact with each other most days or at least every week. Good friends most weeks or at least every month.

These numbers are helpful to consider when building learning experiences. And also designing the cross-functional teams that deliver them.

Dunbar’s numbers for learning

As those involved in learning already know, different learning activities are more or less successful in different sized groups.

But Dunbar’s numbers help to bring some order to understanding why this is and is a useful tool to think through how to construct different experiences.

For example, consider which activities are best done:

On your own, at your own pace

In small groups of five where you can collaborate on group activities, team projects, group coaching

A small cohort of up to 15 is a safe-space to share and explore new ideas with support and accountability

A large cohort of up to 50 where there is diversity amongst friends

A group of 150 with a shared purpose and sense of being part of something bigger but still with recognisable names and faces

I would argue that, much like how diversity in different learning activities and modes of delivery is important to create more effective and engaging learning experiences, so does having a range of activities that happen in different sized social groups.

Self-paced learning typically isn’t effective done in isolation. People lack accountability and support. Only the most determined are likely to complete an experience of any length or complexity. This is the problem with MOOCs as they have tended to on-demand. But self-paced learning adds flexibility and enables personalisation and so is an important component.

Similarly, delivering lectures or webinars to large groups isn’t very engaging. But the sense of shared purpose and being part of something bigger can be motivating. And it can make things more efficient.

In my adventures in edtech, I’ve reached the conclusion that the most effective learning experiences are ones that combine:

the flexibility of self-paced learning on your own

doing learning activities where there is the psychological safety, support and accountability of a small cohort (~15)

with opportunities to be able to put things into practice in small groups (~5)

within a larger community that provides diversity, reassurance and purpose (50, 150)

Dunbar’s number for teams

Similarly, it’s worth considering these numbers when designing the cross-functional teams that deliver the learning experiences.

‘Loved ones’

To maintain alignment, speed, trust and a shared sense of purpose, don’t make cross-functional teams that work together on a daily basis to tackle complex problems bigger than five.

The kind of work I call pioneering work, which requires a small nimble team with different expertise. This might be creating a new app or learning experience.

Similarly, if you have a group of experts working together on some deep technical work with a clear outcome - architecting work - keep the team small. Something like curriculum design or moving to a service oriented architecture.

I would also suggest that for exec teams to be most effective, consider limiting them to five to ensure that they are having hard conversations with a high degree of trust.

And if you’re a line manager with other responsibilities, it’s hard to manage more than five people.

‘Good friends’

If you’re your working on new solutions to a better understood problem - once you are improving and scaling something new and doing iterating work - then you could consider growing the team up to 15.

Or if you have a team engaged in more predictable delivery work. Like marketing or sales campaigns or running a programme.

This is also a good sized group for communities of practice to run sessions like design critiques or review architectural type decisions.

In larger organisations, this might size might also work the broader leadership team where it’s important that all teams are represented and voices are heard.

It’s still a safe space to share.

This also might also be the maximum number of people you can effectively coach or manage if your role is exclusively looking after people in a role like an engineering manager. It’s hard to hold more people in your head.

‘Friends’ and ‘meaningful contacts’

Breaking 15, 50 and 150 people are big milestones for organisations. These are moments when you are likely to need to redesign how you organise and communicate.

When things need to start to be written down and communicated in more formal ways, rather than just by osmosis. Where it becomes helpful to move from implicit to explicit hierarchies, roles and responsibilities.

The Gore-tex clothing brand and Swedish Tax office split business units into two when they go past 150. That way folks still know who to get in touch with in the marketing team for example. People can maintain relationships.

Emily Webber who writes good things on communities of practice has also researched and reflected on the implications of Dunbar’s number. Her research suggests that organisational groups mimic natural social communities:

Groups of less than ~40 report a greater sense of camaraderie and can be more democratic. Beyond that you need more formal leadership

Smaller communities or sub groups are able to more easily carry out focused activities and tasks

On average, groups of 5 meet roughly every 13 days, groups of 15 every 24 days and groups of 150 46 days

All this suggests that, as with designing learning experiences, thinking deliberately about the activities your team does, how often they do them and the size of the group that they would be most effective within will pay dividends on how successful you will be.

To explore this further, check out this article on the BBC about Dunbar’s number, including its detractors and Emily Webber’s research into the size of Communities of Practice.

I’ve referenced my definitions of kind of work - you can read more about here. I also once did a talk entitled Be In A Band Not An Orchestra about growing cross-functional teams that brings this to life by explaining how we grew and organised different groups at FutureLearn.

I’m exploring building a new fellowship programme on building cross-functional teams. Get in touch if you’re interested to find out more.