How to discover new learning products

How do you go about finding new opportunities and developing solutions in EdTech? Part three of my series on product thinking for learning products.

🧩 This is part three of my series on product thinking for learning.

“Don’t find customers for your products. Find products for your customers.” - Seth Godin

This quote brilliantly sums up the mistake that is so often made when developing new products. This is often the case, but perhaps more so in education.

Entrepreneurs typically see a way to solve a problem and want to sell it.

Educators are passionate about their thing and want to teach it.

And thinking about solutions is a natural instinct for humans.

But this immediately gets us off on the wrong foot when it comes to creating educational experiences that solve real problems for real people.

Instead of falling in love with our solution, we need to focus on the outcomes for learners.

Outcomes

Outcomes is a much used word in education. Often teamed with learning. Learning outcomes. However, these are often regarded as a bureaucratic nuisance. Something to retrofit to the thing you want to do, rather than the guiding principle.

But to find product-market fit for learning experiences we need to focus on the outcomes. What do our learners want and need?

In order to do discover this we need to do research. Research helps us understand:

What learners want and need. This is foundational research.

What solutions currently exist. This is market research.

What social, regulatory and technological trends might enable new solutions.

All of these kinds of research are about uncovering opportunities.

Opportunities

Opportunities are the connective tissue between outcomes and solutions. If you know the outcome you’re hoping to achieve then you can start to explore opportunities to make it happen.

There are many forms of foundational research. This is typically ethnographic and includes things like diary studies and observing people in their context. But the simplest form is interviewing and using techniques like Jobs To Be Done (JTBD).

The goal with JTBD is to uncover when people are in a certain situation, what motivates them to do something and understand their expected outcome. It helps you see how they currently achieve this, or the things they are considering and why.

It also helps highlight where there are opportunities to do this better. In JTBD lingo, why they might ‘fire’ the current solution and ‘hire’ an alternative instead.

If you recruit well then you need surprisingly few of these conversations to start to see clear themes emerge.

Note, that you’re not asking them what they want or what they think they need. People rarely know this or will give good answers. Particularly when it comes to what they need to learn or what will help them do it.

Instead it’s about uncovering the needs through getting them to describe situations of things they have done or considered in the past, not what they think they will do in the future, digging into why and then spotting the opportunities to do it better.

This sort of research enables you to start to map out the opportunities that might achieve their desired outcome. You can start to prioritise these opportunities by combining them with insights about the market, trends and your team’s capabilities.

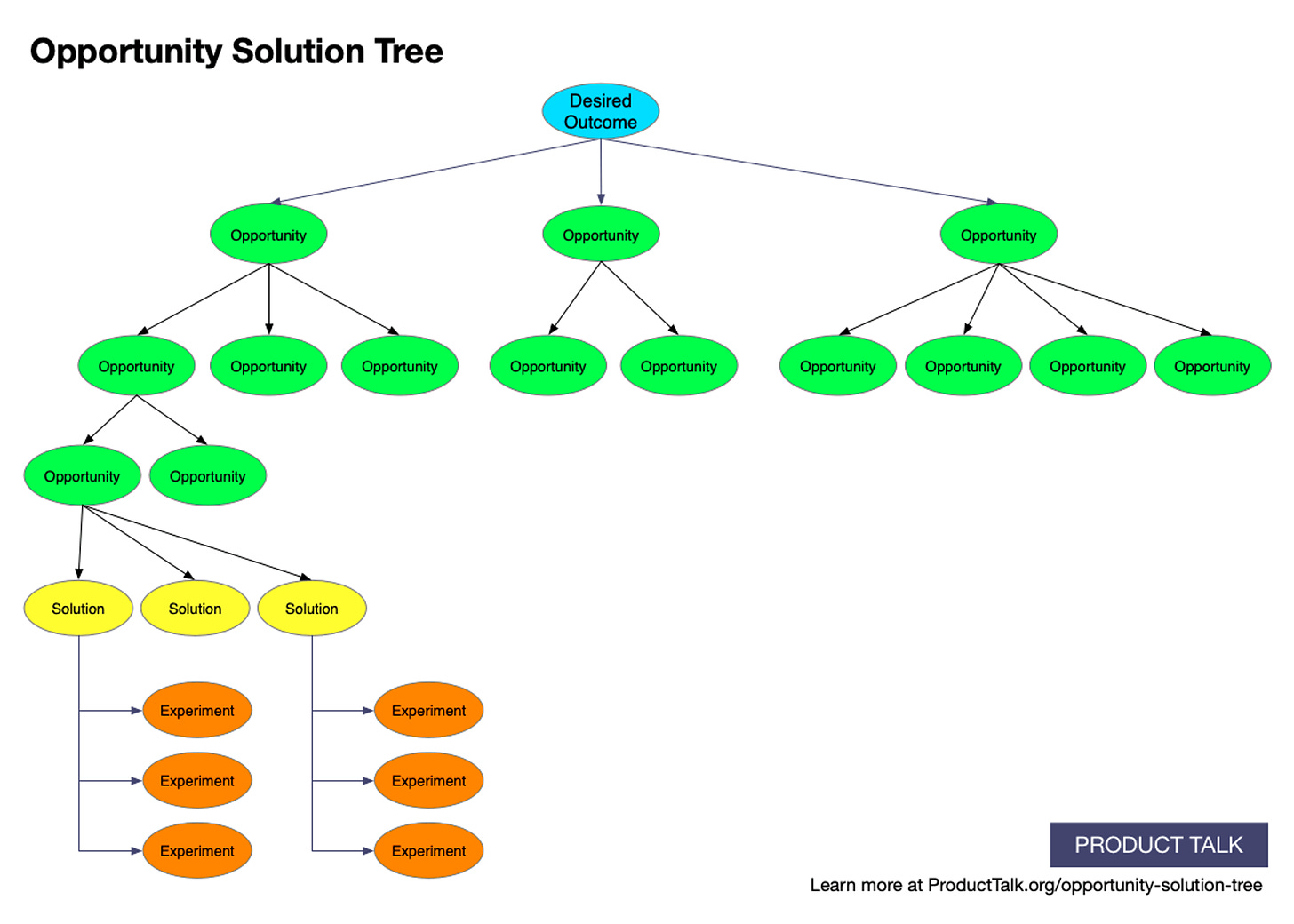

A useful tool to start to visualise this is Teresa Torres’ Opportunity Solution Tree.

Solutions

Once you understand the opportunities, the next step is to prioritised a specific branch. You can’t do everything at the same time. But you can come back if you find it’s a dead end. Once you know what opportunity you’re focusing on, you can then start to think about potential solutions.

But rather than just developing one, try and develop several different approaches to the tackle the same opportunity. And then find the quickest way to test them and find out if they work.

This is directional research and often know as an experiment or a Minimum Viable Test (MVT).

The trick with an MVT is to identify your riskiest assumptions and then test an ‘atomic unit’, before investing too much. Each experiment should further your understanding.

This can be tricky in edtech if you’re trying to test something that happens over a long period of time as learning often does. But you can do things like test a shorter learning experience or a landing page describing a bigger thing and gauge reactions.

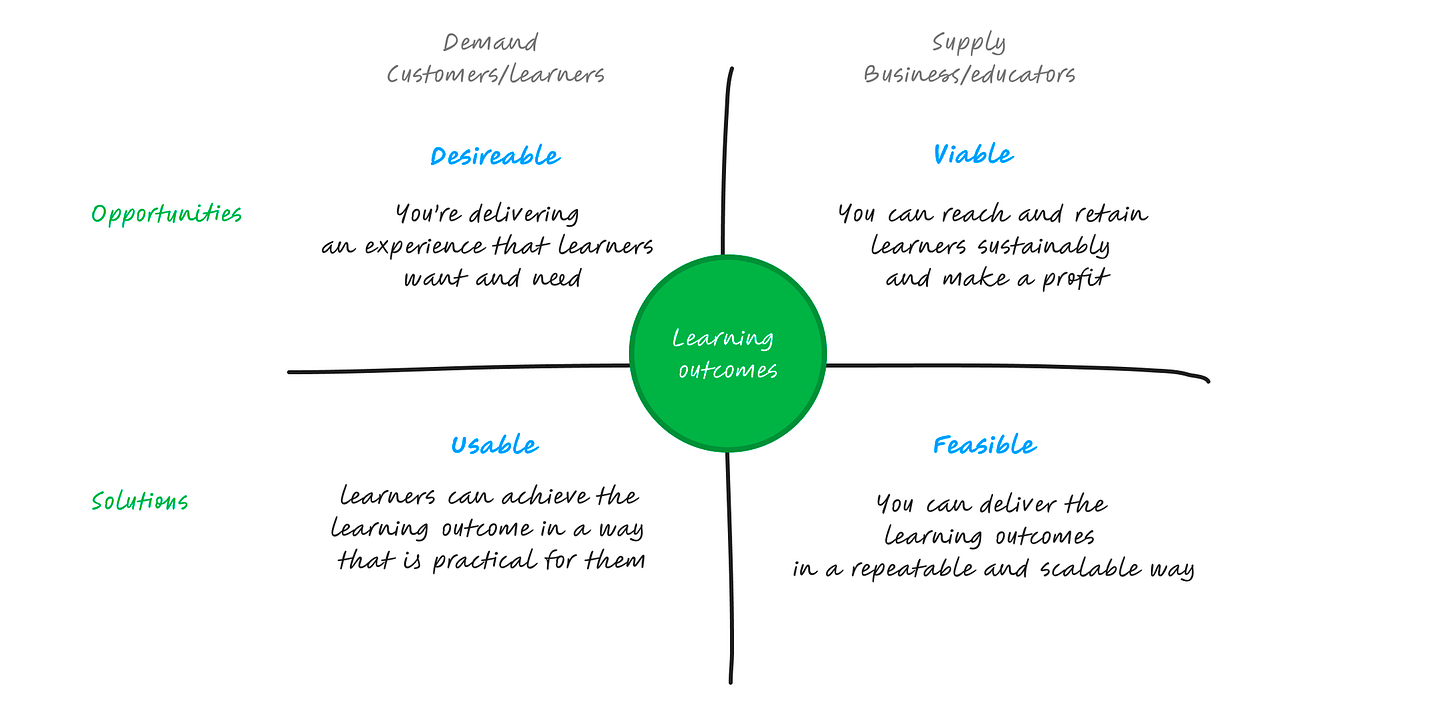

Opportunities, solutions and DVFU

In the last two articles, I talked about creating learning experiences that are:

Desirable: You’re delivering a learning experience that learners want and need

Viable: You can reach and retain learners sustainably and make a profit

Feasible: You can deliver the learning outcomes in repeatable and scalable way

Usable: Learners can achieve the outcome in a way that is practical to them

👆 Opportunities are about the top two: discovering a desirable experience that learners want and need and understanding the market in order to understand if they are viable.

👇 Solutions are then about finding usable and practical ways to deliver it in a way that is feasible to deliver in a repeatable and scaleable way.

If you can discover the right opportunities and then deliver a great solution you can achieve the learning outcomes.

Bringing it to life

At this point, it all might be sounding quite theoretical. So here’s an example from the work I did with The London Interdisciplinary School (LIS). My brief was to explore what else LIS could offer beyond their BASc undergraduate programme to help bring scale and revenue as well as further their mission.

Outcome

LIS’s mission is to help people tackle complex problems by taking an interdisciplinary approach. This was the high level outcome.

Finding opportunities

We quickly mapped the landscape of opportunities - different kinds of content, form, mode, customer etc. - and started to interview people within the LIS network: students, employers, people signed up to the newsletter to understand where there was appeal.

From these conversations, by looking at trends in the market we started to identify and prioritise various opportunities. We also considered where we had expertise.

Testing solutions

We then tested landing pages for various propositions:

Problems: Climate, Urban, AI

Methods: An interdisciplinary take on data science

Roles: Leadership

We bought Google Ads and could see the volume of impressions, how many people clicked through, how long the spent on the page and if they registered interest. Then reached out to those that had registered interest and interviewed them. We also pitched these programmes to various businesses to understand reaction and appetite.

And we ran short open programmes on AI and Cross-functional Leadership and worked with a couple of business on a Climate proposition.

Alongside this, we explored different specialisations and form factors for the new Masters programme via a register interest page, survey and more interviews with potential as well as current students.

Insights

Out of this activity we discovered several key things:

LIS’ appeal is breadth. Potential students come to explore different perspectives and find their problem. And unlike other Masters programmes, it allows them to keep their options open. Specialisation undermined our USP. (Desirability)

We lacked expertise and credibility to deliver highly specialise programmes - there are other places you would go if you’re specifically interested in climate or data science. (Desirability and feasibility)

Leadership, specifically Cross-functional Leadership, had strong appeal and people were fascinated by an interdisciplinary approach. (Desirability)

The acquisition costs for short programmes is high and margin relatively low. Plus, LIS’ distinctiveness is as a new institution with degree awarding powers. (Viability)

Most students want a combination of flexibility and to be part of a community. LIS attracts people who actively seek out new people and perspectives. Online or campus degrees is too binary. But some want an intensive experience and some want to learn alongside other commitments - and there appeared to be more of these. (Usability)

Businesses are slow and hard to work with and the cadence and demands are hard to manage alongside delivering undergraduate programmes. (Feasibility)

Strategy

This enabled us to develop a clear focused strategy:

Focus on direct-to-consumer, long form, accredited programmes

Teach an interdisciplinary approach at three stages: undergrad, masters, leaders

For Masters, offer a part-time mode that is remote-first, alongside full-time campus first mode that both offer a hybrid of online and campus

It also helped us avoid investing too much in designing programmes that failed to meet the DVFU criteria.

Product discovery and product-market fit

In my second article in this series I quoted Marc Andreessen’s original essay on product-market fit:

“In a great market — a market with lots of potential customers — the market pulls the product out of the startup.“

This doesn’t happen on it’s own. Product discovery - the sort of process that I have described above - is the means by which you can do this systematically. Focus on outcomes, uncover opportunities and test lots of solutions. That way leads product-market fit.

💬 Try creating an opportunity solution tree. What outcome is at the top? What opportunities do you already know exist? Are you testing enough solutions?

Next time, I’m going to look at the role of product management and cross functional teams in the world of learning.

If you’re curious to go deeper, I run an 8-week fellowship programme helping you apply these ideas to your project.